Critiquing the Major Film Studio Logos

About 90% of the money paid to see a movie in North America goes toward one produced or distributed by one of the six “major” film studios. These are mega-profitable, highly visible corporations that nevertheless usually don’t have a lot of brand distinction between them. A movie is a movie is a movie, for the most part, and I don’t know anyone in today’s world who associates any one major with a particular type or quality of product (with the one exception probably being Disney). Yet each company has a rich history and an identity they try to convey to indifferent viewers, probably more for the sake of tradition and corporate pride than for advertising or branding purposes. The way they do that is through their animated logos which they slap in front of their releases. I decided to examine these little-scrutinized industry totems and review those of the six majors. Here are my conclusions:

Columbia Pictures

Columbia’s logos over the years have varied as to whether they zoom in to or out of the torch’s light, but all have featured “Columbia,” who looks exactly like Annette Bening, and is supposed to be a female personification of the United States. (A little ironic for a studio owned today by Japanese conglomerate Sony.) The latest iteration, which has been in place since the early ’90s, contains some rich detail and color, especially in the clouds. I think it would be cool if those clouds were animated to move in a more noticeable way, but it’s still an impressive feat to make clouds so visually interesting. This logo also features a lens flare big enough to embarrass J.J. Abrams, which was certainly not the case in the logo’s early years, when lens flare was thought of as an unacceptable error rather than the cinematographic weapon it is today. Although the scene is presented about as attractively as it can be, this logo feels a little off to me. Its patriotism, even after being toned down—the blue drape Columbia holds used to be an American flag—doesn’t seem all that relevant to the idea of movies; the symbol isn’t evocative of much other than silver dollars and World War I propaganda. I really like, however, how the studio lets their mascot have fun: She wears sunglasses and holds a neuralyzer for Men in Black, and in a bizarre meta-joke, had her face replaced with that of the real Annette Bening for her 2000 film What Planet Are You From.

Paramount Pictures

Like most of the logos in this list (movie studios rarely go with a full re-brand, I’ve discovered), the Paramount logo has changed from one variation to another of the same theme for the entirety of the studio’s existence. I had always assumed the mountain depicted was supposed to be the Matterhorn, but it’s a bit too misshapen, and possibly a bit too associated with another company, to be it. The logo’s original designer was a Utah native and many have suggested it could have been inspired by any number of peaks in the Wasatch Range. But if there’s one mountain in the world that most resembles the Paramount peak’s current form, it has to be Peru’s Artesonraju. Anyway, the identity of the mountain is irrelevant; the question is, how does it function as a logo? I would say this logo does a lot with relatively little, and the stars that ring the mountain are the unsung heroes here. For decades, their appearance came spontaneously. Starting in 1986, they approached from downstage right. And after 2002, they descended from the heavens. As you can see in the logo above, the new 100th anniversary one adds some new wrinkles including the stars taking a meandering, leisurely skip across a lake and a bright sun in back of the mountain. I give Paramount credit for making such an obtuse, formerly static symbol interesting. It doesn’t have much to do with movies or anything else really, but something about it just feels right.

Twentieth Century Fox

The monument topped with a huge “20th” predates the company itself, as it was originally used by Twentieth Century Pictures before its merger with Fox Films in 1935. The gleaming Art Deco colossus is a splendid thing to center a movie studio logo around, because it belongs to a certain design era that everyone associates with Classical Hollywood. Until 1994, the image was stationary; only after then was the twirling view of a CGI Los Angeles cityscape introduced. The first iteration included a number of easter eggs to be found in the signage on buildings, including, for instance, “Murdoch’s Department Store.” The version seen above was updated within the last few years but is largely unchanged, as the most visible difference to the old CGI one is the addition of palm trees surrounding the spotlights. I’m wholly in support of this. The more classic Hollywood tropes they can cram in there, the better. I like this logo a lot because it’s sort of like a slightly more reality-bound version of the new Disney one. In this case the fantasy world isn’t one of medieval legend but an idealized, romantic Hollywood, and it feels alive, with individual buildings and moving cars and the Hollywood sign. I think they could probably do more with the idea—how about throwing in a majestic old movie palace marquee or two?—but I still think this is one of the best studio logos there is.

Universal Studios

This is one logo that has benefited a lot from the development of CGI in my opinion. Its extraterrestrial vantage point was ambitious when it became the first still-operating American film studio to be founded in 1912 (beating Paramount by a few months); early renditions of the logo were obviously of the scale model-on-a-matte-background variety, and it stayed that way pretty much until the ’90s. It was only then that the magic of 0s and 1s could provide the vivid detail we see today. The 100th anniversary logo seen above takes, aside from the huge interstellar cloud it has the Earth residing in front of, a very realistic approach to to the globe. This includes depicting the luminescent signs of human inhabitance, a decision that I’m not sure how I feel about. For sheer aesthetics, I think I preferred the late ’90s and ’00s version with an Earth that was shimmering with white light and comprised of the brilliant rainbow of hues normally reserved for topographical maps. To its credit though, the new one is a tiny bit less Americentric, as it doesn’t conclude with North America perfectly centered. (The Earthcentrism of the company’s name referencing the universe but only focusing on our planet is another issue.) All in all, this is definitely a logo I can get behind. I like anything in space, the globe is an instantly recognizable icon, and the subtextual message—that through movies you can have a world of experiences—is a comforting one.

Walt Disney Pictures

The Disney logo of my youth holds a good deal of nostalgia but it was looking aged by the mid-2000s. Knowing nothing but the two-tone, two-dimensional representation of Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle, the 3D, flag-fluttering version that preceded Toy Story (and a few other Disney/Pixar films after it) was a bit of a shock. But nothing prepared us for the staggering orgy of color, sound and visual information contained within the current Disney logo. It starts in space, focusing on the star to be wished upon from Pinocchio, along with the “second star to the left” from Peter Pan. The camera swoops over an ocean, multiple rivers, an expansive network of small villages, a large sailing ship and a steam locomotive before settling before an amalgam of Sleeping Beauty Castle and Walt Disney World’s Cinderella Castle. I love this logo. If you look really closely, you can see numerous individual buildings and trees, a network of roads, docks extending into the rivers, another faraway castle-like structure, and an entirely different landmass beyond the sea. On its bad days, Disney can feel sterile and like a soulless simplification of everything; that feeling is not to be found in this logo. it presents a breathing universe that represents Disney’s position as a modern custodian of timeworn myths and implies that that universe can be explored and lived in rather than only known of at the basest level. Essentially, I want to play an open-world video game taking place inside the Disney logo, and I’m impressed when any 30-second clip of anything gives me that feeling.

Warner Bros.

Unfortunately, I think there is a clear last place among the six majors’ logos, and it is occupied by Warner Bros. Although they’ve gone through some interesting minimalist periods, the gold shield as we see today has been pretty much the same as long as it’s been their logo. I have a number of issues with it, and the fact that it’s hard not to think of Looney Tunes when looking at it is the least of them. Biggest of all is the opening view of the sequence, in which we see a warped, gold-stained aerial shot of what I presume are Warner’s studios. Like I mentioned with the Fox logo, I applaud attempts to showcase imagery that evoke the essence of Hollywood. But this one fails because there’s nothing romantic, exciting or emotionally resonant about looking at row upon row of warehouse-like soundstages, even if they are where the proverbial magic is made. And it doesn’t help that the image is probably too distant to look like anything identifiable anyway unless you are really concentrating, which you are not, unless you are scrutinizing it on YouTube in order to blog about it. Another problem with this logo is the sky background. Columbia proved that with CGI you can make clouds look amazing. So why is Warner still rolling with what looks like a matte painting from the ’40s? It’s jarring, especially since the shield itself has had a 3D, CGI sheen since 1998. I don’t think this logo concept provides very much to work with compared to some of the others, but I still think WB is really dropping the ball here.

Well, that ends my review of the Big Six, though there are dozens more logos like them in the wide world of film production and distribution, including a few real gems. I think my personal favorite might be that of Skydance Productions, which, for some beautifully inexplicable reason, shows the letters of its name being released into zero-gravity space by elaborate vice-crane contraptions in the vicinity of the Sun. I’m also a big fan of those of Marvel and DC, which in my estimation express a similar idea—the mythmaking power of the comics medium—in admirably different ways: Marvel by overwhelming the screen with the vastness of its canon, and DC by showing rays of weightiness emanating from those iconic building blocks of comics, the Ben-Day dots. Hollywood has been owing much to these companies lately, and I think it could learn a lot from their movie logos too.

The End of Geography (Except, Not)

When I was young I loved maps. (Not that I don’t now; I still spend a lot of time browsing Google Sightseeing, the book of transit maps from around the world my girlfriend and I bought, and reddit/Map Porn.) As a child I had a puzzle of the United States that I would regularly trace, writing in information of limited importance such as the order of their admittance to the Union. I remember being enthralled at my friend’s CD-ROM street map that covered the entire country.

The intersection of Internet technologies and the traditionally geographically diverse nature of sports has created some interesting issues, and for that matter, maps. This one shows what teams are blacked out in what locations on MLB.tv, baseball's out-of-market TV service.

Of course, today we don’t think twice about being able to pull up a comprehensive street-level atlas of the entire Earth on a portable device the size of a Game Boy Light. Anyone could come up with countless examples of how the world has shrunk even more as the Internet has pervaded our lives more and more.

One might think this would mean that physical location doesn’t matter as much as it once did. In some ways, this is definitely true. It’s easy to get into Singaporean politics, Namibian cricket or Greenlandish hip hop while you lie comfortably in your American bed. This huge expansion of the information one can find if they put a little bit of effort into it is one of the things, if not the main thing, that makes me happy to be alive when I am.

But when it comes to the mass media, I’ve noticed an odd thing: It seems today that location means destiny more than ever.

Take national politics, for instance. Coverage of presidential races is now overwhelmingly reported on by 24-hour cable news networks that deliver the same content whether you’re in Hawaii or Maine. Yet political parties worry about the optics of geography more than ever.

Look at where national nominating conventions have been held. From 1992 to 2004 Democratic conventions were held only in liberal metropolises: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston. Since then the conventions for both parties have been swing-state only affairs: Denver and Charlotte for the Democrats, St. Paul and Tampa for the GOP.

Another area in which geography is playing a larger role is television. Scripted TV shows of the past may have had real settings, but the Milwaukee of Happy Days or the Seattle of Frasier were little more than abstract concepts flavoring the L.A. soundstage environments. While there are still some spectacular examples of this—until you’ve seen the Disney Channel’s Wizards of Waverly Place, you have no idea how much Greenwich Village looks like Disney World’s Main Street, U.S.A.—the phenomenon has lessened as single-camera, on-location shows become the norm. And it’s even more pronounced when it comes to reality TV.

The Real World is often cited as a reality pioneer and that holds true in its featuring a different city for every season. Because today, it seems like most big reality franchises are somehow location-dependent. You’ve got Pawn Stars in Las Vegas, Swamp People which inspired a bevy of other shows set in the Louisiana bayou, Jersey Shore which did the same for New Jersey, and The Real Housewives of most conceivable upper-class locales, the format of which is now being exported internationally.

The area in which location seems to have taken on the most added significance recently, though, is sports. ESPN and other national media outlets once acted actually national; now their inordinate focus on teams from the very few largest media markets is unmistakable.

Take the Jeremy Lin phenomenon. I think his is an incredible story and it certainly deserves media attention. But you’ve got people like Mark Cuban—the owner of a team in a big, but not huge, non-coastal market, the Dallas Mavericks—saying that it wouldn’t be much of a story if it wasn’t happening in New York. I’m sure Cuban was exaggerating when he said “no one would know” about Lin if he was playing elsewhere. But it seems clear to me that it wouldn’t have developed into the same obsession for the Worldwide Leader.

Interest in consolidating the NBA’s elite talent into the biggest markets seems to be at an all-time high, if the recent demands of players like LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony and Dwight Howard to be traded only to alpha cities are any indication. It’s hard to blame young men with boundless fame and disposable income for wanting to live in New York, Los Angeles or Miami. But I do blame certain media outlets for encouraging them by focusing so disproportionately on teams in places like that.

North American celebrity culture in the realms of film, TV, music, comedy, and so forth have always been centered around an extremely narrow group of cities. I don’t have a problem with that—after all, that’s part of what gives those cities their unique attractiveness. But I have always thought it was kind of cool how sports, by the nature of its organization, is a glamorous industry that is quite geographically egalitarian. To ply their trade professionally, a baseball player from Miami could go to St. Louis, a football player from Southern California could go to Green Bay, and a hockey player from Stockholm could go to Calgary, and all of these moves would be considered seriously moving up in the world. I don’t like the feeling that we’re losing that idiosyncratic feature of sports with increased emphasis on big-market teams.

In my opinion, this is particularly unfortunate in the NBA, which has a tradition of placing teams in small cities that no other major pro leagues are present in, like Memphis, Oklahoma City, Orlando, Portland, Salt Lake City, and San Antonio. Before securing a new arena deal this week, one such city, Sacramento, came extremely close to losing their team to Anaheim, in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, which has two teams already. Is this idea of stacking huge media markets with ever more teams a sign of things to come? I hope not, but with the media focus on those areas, it would make a perverse kind of sense for the teams.

The way I see it, national media has two choices about how to approach coverage of a nation- or worldwide sports universe. Either they can identify stories from anywhere in the country that they think, if widely publicized, would have the most wide appeal; or, they can act like a local outlet focusing on the teams with, statistically, the most fans, and push stories about these teams onto the rest of the country that might not otherwise care at the same time. I think they choose the latter far too often. Which frustrates me, because in this day and age, I want to revel in the fact that we’re no longer beholden to local newspapers and TV for our information. And I certainly don’t want to feel like our spectacular modern communication technologies are just feeding me a facsimile of that experience, and about a location I might not even care about in the first place.

Living in the age of cyberspace hasn’t made geography irrelevant—if anything, it’s amplified it. Some of the effects of this are positive and some are negative in my opinion, but either way, I find it pretty counterintuitive at first blush. But as a recent study showing that Twitter connections match up quite tightly with airline routes indicated, the Internet serves as a compliment, not a replacement, for the physical world. Methods of communication may shift rapidly, but human nature has proven much more resistent to change.

Pop Culture Mysteries: The Truth is (Maybe) Out There

The media explosion of the past 50 or 60 years has led to a big increase in the amount of what anyone might call art or entertainment. (Not that everyone would find all of it artistic or entertaining, of course.) The invention of all our familiar mass communication technologies enabled that, and I revel in living in a world that’s completely flooded with pop culture. Come to think of it, that’s sort of a crucial theme to this blog.

What I think might be overlooked is that not only has a great deal of culture been created in this time period, but so has a stupendous amount of information relating to that culture. We’ve formalized things in a way that probably didn’t seem necessary or practical in past eras. It’s interesting to imagine what a medieval lute player would think of Slayer or what the Knickerbocker Club would think of modern baseball. But I also wonder what they’d make of the 117 different Billboard charts or a college football ranking system that takes into account six different computer-generated data sets.

Details play into our understanding of culture more and more, and Wikipedia and the Internet in general put them at our disposal with a minimum of effort. The ease with which facts can be learned has made it possible for netizens to be obsessed with ever more specific minutia. There are dusty Web backwaters where you can learn all about every conceivable piece of Calvin and Hobbes merchandise. About the lifetime winning percentages of all six Legends of the Hidden Temple teams. About the academic validity of the writing on blackboards in school-set pornographic films.

One side effect of all this, for me anyway, is a heightened fascination with those facts that still manage to fall through the cracks. If you have a basically proficient command of Google and something is still a mystery to you, chances are it is a mystery to society as a whole. Unsolved pop culture mysteries remind me of the vastness of time, in the face of a world where we expect nothing to still be hidden. Here are a few of the ones I find the most intriguing.

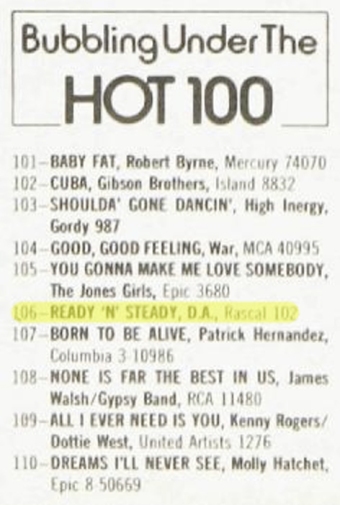

What was “Ready ‘n’ Steady,” and what happened to it?

Joel Whitburn is a meticulous record collector and researcher whose mission it is to own and catalog every record that has appeared on the Billboard singles charts since they were invented in 1958. He now has them all, except one.

D.A.'s "Ready 'n' Steady" bubbles under the Hot 100 on June 16, 1979, then bubbles its way into oblivion three weeks later.

For three weeks in June 1979, a song called “Ready ‘n’ Steady” by an artist called D.A. appeared on the “Bubbling Under the Hot 100” chart (which was, at the time, simply positions nos. 101-110). It debuted at #106, went to #103 then #102, then dropped off the chart—and apparently off the face of the Earth.

No one is known to own a copy of the record or know what the song or artist even was. Whitburn, the authority in this area who has tracked down literally everything else, is totally stumped. He now says he isn’t sure whether the record exists at all.

But the evidence is right there. What makes the “Ready ‘n’ Steady” mystery especially confounding is that for a song to come close to the Hot 100 a song has to be, you know, popular. That no one would own or have much knowledge of, say, a legendary unreleased track like “Carnival of Light” is unsurprising. But songs get on the Billboard charts by having their records bought and being played on the radio. People have to have bought it. Radio stations have to have a copies stashed in their libraries. Someone has got to at least remember the damn thing, right? …Right?

There is one other possibility, one that would be pretty bizarre, though maybe no weirder than a charting song disappearing without a trace. That would be that the song never actually existed in the first place. Who knows why or how a fictitious entry could make it on the chart (for three weeks at that). Could it have been a copyright trap to determine if someone was copying their information? Mapmakers add fake towns to their maps for this purpose sometimes, but since Billboard wants its proprietary chart information to be repeated as much as possible, I don’t see how this could be. Could it have been an inside joke by a rogue Billboard employee? You can’t rule it out, though if that was it, they really should have thought harder about making up a jokier sounding title.

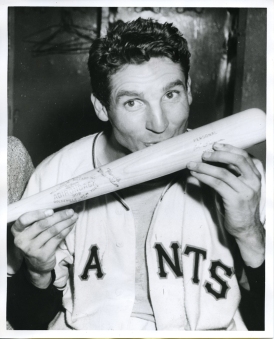

What happened to the “Shot Heard ‘ Round the World” ball?

On October 3, 1951, a legendary baseball moment occurred. Down 4-2 in the bottom of the ninth inning of a playoff game to determine the National League champion, Giants third baseman Bobby Thomson hit a three-run home run to end the game, defeat the rival Dodgers and propel his team into the World Series. It was a shocking turn of events that enveloped the Giants’ home stadium the Polo Grounds in complete bedlam, with Giants fans rushing onto the field in a state of euphoria.

Lost amid the insanity was the fate of one crucial object: the ball. It landed in the left field bleachers and hasn’t surfaced since.

The bat that Bobby Thomson used to hit the "Shot 'Heard Round the World" is in Cooperstown, but the location of the ball is a mystery.

There have been many conflicting stories. One man claimed the ball had been given to him as a child by a family friend, and the ink on it indicating it as such was determined to date from the period. Two eyewitnesses who are visible in photos of the event testified that they saw an African-American boy catch the ball in a glove and run away. An obscure book from the ’50s claimed the ball ended up with a woman named Helen.

One of the most intriguing accounts came from filmmaker Brian Biegel, whose film and book “Miracle Ball” present fairly convincing evidence that Helen was, of all people, a nun. This Sister Helen insisted all her possessions (including, presumably, the ball) be thrown into a dump after her death, and Biegel suggests this was because she was breaking the rules of her order to even be at the game in the first place.

That there’s recently been so much interest in finding this “Holy Grail of Sports” and that in 1951 whoever ended up with the ball didn’t think it important to come forward then or possibly ever, shows how much the concept of memorabilia has developed. Antiques Roadshow, eBay, Pawn Stars and other cultural elements emphasizing the collectability of things has transformed the significance we place on historical objects, and probably on contemporary objects as well.

What’s so interesting about that is that this is all happening right as objects would seem to mean less than ever before, in the age of e-books, mp3s and paying at Starbucks via mobile phone. I wonder if all this has alerted people to the increasingly few things that cannot be digitized. Historical items fall under that category of course, and I’d bet that as society grows more and more digital historical objects will grow more and more interesting to people, as the very concept of tangibility becomes more alien.

There are other mysteries in the world of antiques and collectables, but none about something so crucial to American pop culture. Indeed, Don DeLillo’s magnum opus Underworld immortalizes the whereabouts of the ball as mythic. Huge industries have sprouted up recently dedicated to knowing the truth about old things. But deep down, perhaps even subconsciously, I think people yearn for there always to be a bit of mystery concerning the past. And the chances that the Shot ‘Heard Round the World ball will ever leave that realm seem very slim to me.

What is the origin of the vocal sample in DJ Shadow’s “This Time”?

I’ve discussed music sampling on this blog several times before. And while I’m disturbed by some of the more shallow uses of the technique, I’ve also mentioned some artists whose sampling I think is really artistic and interesting, such as “plunderphonics” groups who construct entire albums solely out of obscure vinyl samples, like the Avalanches. A similar if less dance-oriented artist who preceded the Avalanches is DJ Shadow, who the Guinness Book of Records credited with creating the world’s first completely sampled album with 1996’s Endtroducing.

Ten years later, DJ Shadow released a tepidly received album called The Outsider that was a good deal less sample-crazy. But its lead track, “This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way)” was built around one of the most peculiar samples ever.

Puff Daddy may have been happy to copy Led Zeppelin and the Police, but it’s apparent that more creative DJs try to outdo one another in finding the most obscure samples possible. The vocal sample on “This Time,” however, might be some kind of trump card, because no one, including DJ Shadow himself, knows who it is.

Apparently, it was found on a demo reel in an abandoned studio in the San Francisco Bay Area, labeled only with the name “Joe” and the year 1967. If Joe, or anyone who was aware of him making this recording, is still alive, they either haven’t heard this song or haven’t come forward.

The genesis of DJ Shadow and Joe’s track is a testament to the power and mystery of recorded media. How amazing, and strange, is it that a person can write a song and lay it down one day only for it to be both forgotten yet preserved, awaiting rediscovery without any of its original context, for decades?

Considering how much people know about obscure vinyl recordings—the videos breaking down the samples in Avalanches and DJ Shadow songs linked earlier attests to that—something like “This Time” makes you realize how much in fact how much culture we don’t remember. How much has been lost, forgotten or as of now hidden is, to me, incredible to think about.

What is “It doesn’t DO anything! That’s the beauty of it!” from?

Take a look at that quote. Does it sound familiar? I asked this question of six or seven friends and they all said it did. Apparently people across the country and world all do. So…what is it from?

Can you place it? Don’t worry. No one can. It has bedeviled the Internet for years and some truly epic attempts to figure it out have been made to no avail. Willy Wonka, the Simpsons, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy—some guesses are more prevalent than others but nothing has proven correct. Investigators have scoured deep into the annals of pop culture looking for the line, and occasionally something reasonably close from a source that is today mostly obscure like this will show up.

Of course, that misses the point. The seeming ubiquity of “It doesn’t DO anything! That’s the beauty of it!” ensures that it can’t be from something most people are not likely to have seen. Chances are that it sounds familiar to everyone because everyone has heard something that sounds similar to at least part of it somewhere. Why this particular phrase has such a strong associative effect like that, and furthermore how and why and by whom it reached the public consciousness for being such, are sub-mysteries of their own.

I think this one is amazing because it’s a mystery so mysterious that it strongly challenges one’s perception of the mystery’s premise in the first place. It’s probably not truly a question seeking an answer at all, it’s more likely a vast sociopsychological phenomenon that creates a mystery without any any possible solution. You can try and try to find the answer, but ultimately you really can’t do anything with this one. And you might just say that’s the beauty of it.

What Might ’00s Nostalgia Look Like? An Exercise in Future-Retroism

There’s no way to confirm this empirically, but it feels to me like ’90s nostalgia has exploded in just the last year or so. Nickelodeon announced an upcoming ’90s nostalgia programming block, NBA jerseys of the era are all the rage, and amazingly excellent blog posts that you should read are being devoted to its cultural relics.

Of course, this should not have surprised me. As I mentioned in the kids’ sports movies post and as others have pointed out, nostalgia for a decade begins two decades after it like the clockwork of this watch (see? ’90s nostalgia is inescapable all of a sudden!).

So we know ’90s nostalgia is big right now and will likely only get bigger as the ’10s go on. Trust me when I say I approve of that. But for this post, I want to try to travel into the future. To 2020, to be exact, when according to the aforementioned ancient Mayan nostalgia calendar that hasn’t been wrong yet, nostalgia for the ’00s will kick into gear.

You might find it hard to imagine, today, what anyone could be nostalgic about, and I’m right there with you. But I have no doubt that no one in 2001 really knew what kind of form ’90s nostalgia would take at the time either. While acknowledging that difficulty, I’m going to attempt to predict, at this very early time, what ’00s nostalgia might look like.

How will I do this? Not very well, is likely to be one answer. But as for my methods, I think there’s enough to be learned from the common themes in the well established ’70s, ’80s and now ’90s nostalgia movements/industries to develop certain nostalgia indicators, if you will.

I think a key thing that characterizes objects of nostalgia is that they are often not the cultural items that are considered actually great. I don’t think anyone says “I love ’70s movies, like, ‘The Godfather.'” That’s not to say they necessarily have no actual merit, it just means they might be things that don’t immediately ensure cultural endurance.

In that way nostalgia is a concept that shares a lot with the tenets of pop art. It’s as much about resurrecting what’s been discarded as it is about determining what had merit. Something from the past that satisfies both these conditions will quite likely be deemed nostalgic. Something discarded that wasn’t all that good has a decent chance too. And even a few things that endured because they had merit might, but only if they are extremely indicative of their time.

So based on those ideas and what I know of contemporary nostalgia, I will attempt to figure out what from several different areas of culture in the ’00s will be viewed as such. You might have heard of retro-futurism, the artistic concept of utilizing motifs based on what the future was thought to possibly be like in the past. This is going to be the opposite. Join me now, as I take a future-retroistic journey to 2020…

The first thing I’d like to discuss is the Internet. I think the few years after 1995 when the Internet was truly a wild frontier, the “Netscape Era” if you will, is pretty fascinating. But I feel sure that in the future the ’00s will be seen as the golden age of the Internet.

The Internet is becoming more and more the media norm every day. If the 2012 presidential election is not the last one to be covered in newsprint, I think the 2016 one definitely will be. Every facet of Internet media has gotten more corporate and slickly produced, from digital editions of newspapers to YouTube to the way music is downloaded.

The ’00s will end up looking like a pretty special time in Internet-land: a time when blogs were vibrant and mostly noncommercial but still well read and commented upon, when social networking became an exciting new youth-driven thing, when a whole new culture that would eventually take over the worldwide mainstream really began to take root.

I imagine this shirt could be a prime example of ’00s Internet nostalgia. So could lolcats or any other meme that seems indicative of the time before the Internet really “grew up.” Hell, I think computers themselves could be items of nostalgia by 2020. I don’t want to give any support to Apple’s suggestion that the iPad is “magical and revolutionary.” But I do think the combination of tablet PCs, ever more powerful smartphones, and the fact that the Internet will probably be ingrained into almost every product might make the concept of hunkering down with your laptop a thing of the past.

I wanted to mention the Internet first also because I think its presence will affect future nostalgic views of many other things too. Which brings me to TV. Similarly to what I mentioned about computers, I feel certain the idea of watching a show at a specific time because that’s when it airs will be extinct pretty soon. You can already see this happening everywhere, what with Hulu and Netflix streaming and so on, and of course we have the Internet to thank for those wonderful things.

As for the actual content of nostalgic ’00s TV, I could imagine reality shows that are starting to taper off in popularity a bit like Survivor (currently in its 22nd season, by the way) being a big part of it, especially if reality shows are not the networks’ bread and butter anymore by 2020.

But the most fervent nostalgia comes from those were young during the decade in question. There’s moderate ’90s nostalgia for Friends or The X-Files, but extreme nostalgia for everything Nickelodeon did in the decade. And what is the equivalent in the ’00s? I think the answer is the Disney Channel. That’s So Raven and Phineas and Ferb will be seen then the way Clarissa Explains It All and Doug are now. Of course, future Nickelodeon-style nostalgic shows could also be from…Nickelodeon itself, which has still been the most-watched basic cable channel for years.

And I have to disclose that the inspiration for this post came from when I was thinking up a trivia question about The O.C. and was amazed at how evocative of a different time it felt, despite the fact that it only debuted eight years ago. I couldn’t quite place my finger on exactly why that was, but it probably had something to do with the endless stream of indie rock that was on display.

“Indie” music (I put that in quotes because “indie” became just a genre, not really a reflection on the type of label one was signed to) will, I imagine, become a large part of ’00s music nostalgia. And while a lot of it doesn’t really rock that hard, the truth is that by 2020 we might be long past hearing anything that could be considered “rock” at all in the mainstream.

As for ’00s pop, if you ask me which pop stars will be objects of nostalgia and which won’t, I can’t say confidently except that I feel certain Britney Spears is going to have a huge revival at some point. She has every element of future nostalgia written all over her: enormous initial success, a long descent into being tabloid fodder and not particularly culturally relevant, but a past repertoire of sugary pop gems waiting to be re-appreciated in the future.

To return to indie rock for a second: While Death Cab for Cutie and the Shins may have been featured in the preppy world of The O.C., the indie movement they represented was inextricably linked to hipsterism. Love them or (as almost everyone seems to profess, even if they seem to be one) hate them, I think in the ’20s they could very well be seen as the definitive fashion trend-setters of the ’00s.

A common criticism of hipsterism is that it is a regressive culture, concerned only with recycling stuff from the past, and while that might be true, I don’t think it means it hasn’t produced distinctive fashion elements. Enormous glasses, skinny jeans, beards—I suspect all these will be revived as ’00s style in the future.

Another hipster-begun trend is the aforementioned wearing of ’90s NBA jerseys. I am not immune. And while thinking about this post, I decided to purchase, on eBay for $1.25, what I thought will be a future item of ’00s nostalgia. Although recent events make the Sacramento Kings’ imminent relocation look less likely, the point remains: defunct teams ALWAYS become objects of nostalgia, with a fervor that certainly outstrips people’s feelings toward those teams when they were around. (If you don’t believe me, check out the winning bid for this item.) So expect teams that are likely to be moved soon, like the Kings or the Phoenix Coyotes, to be treated the way the Vancouver Grizzlies or the Montreal Expos are now.

I think it’s interesting that the hipster jersey trend focuses mostly on basketball rather than other pro sports; I’m guessing this is because the ’90s were when the NBA really settled in as a global presence after its big gain in popularity in the ’80s. (Space Jam, whose sublimely ’90s website is still online, couldn’t have hurt either.) Will one particular sport dominate ’00s nostalgia?

I don’t think it will be hockey, despite it having an interesting journey this decade from positioning itself as the game of the future to almost going extinct after the devastating cancellation an entire season. I also don’t think it will be baseball, which seems like it can survive and thrive through anything, including steroid scandals.

I think if there is one sport that might attract nostalgia in the ’20s it could be football. And the reason I say that is because football might be poised for a decline in popularity over the next 10 years. The brutal toll the game takes on its players in the form of concussions and other injuries, all too often leading to serious problems later on in life, has been coming to light recently. As this column points out, it would not be surprising for football to go the way of boxing, going from dominant to fringe as the sport’s dangers become more and more well known. I suspect that if that happens, vintage NFL jerseys will gain a certain nostalgic quality as totems of a cultural element that was once dominant before a fall from grace.

And speaking of people who fell from grace (even if they didn’t deserve that grace in the first place), let’s talk about the defining political figure of the ’00s, George W. Bush. No, I don’t think in the future Bush will become thought of warmly by the general public, but conservatives will surely try to Reaganize him. And in a way that will be appropriate, because I think the political culture of the ’00s will be seen very much the way the ’80s are now.

That is to say, as a nation gripped by a moderately irrational fear of a less-powerful-than-they-seem enemy. Just swap out the Soviet Union with terrorists. I think we’ll look back and laugh at ourselves for having to take our shoes off at the airport and that this will be reflected in lighthearted movies taking place in the decade. That being said, I think compared to the ’80s this element of ’00s nostalgia will be a little less pronounced, mostly because the terrible events that did transpire were realer than the Cold War was. This shirt and this album cover/band name might be possible today, but I doubt there will ever be a band called “Alan Qaeda and his Qaedets” or something.

Before I finish this post, I want to add a brief coda about one thing. I seriously think there is a possibility that ’00s nostalgia could be less profound than that of the ’70s, ’80s or ’90s, but not because anything about the decade lends itself to being anti-nostalgic, because I don’t think that’s possible. No, I think that could happen—I know it sounds silly, but I am being serious here—because there is no agreed upon way to say “’00s” in speech.

“Aughts,” “Naughts,” “Ohs,” “Zeroes”—all are logical in their own way, but none have the inescapably understood meaning that “nineties” does. Without this universal shorthand, might someone not bother trying to describe something to someone else as being very “’00s”? Of course, that assumes everyone will not come to agreement on a term at some point, which seems unlikely given that none was reached during the decade itself, but not impossible.

Personally, I vote for “two-thousands.” It makes the most sense to me since you begin the spoken form of each year in the decade with those words, and I don’t think ultimately it would be confused with the term for 2000-2099, since if precedent holds the century will be known as the “twenty-hundreds” anyway.

The ’10s don’t have an obvious way to say them either (“teens,” I guess) so write down these three things to look forward to in the ’20s: a clear and obvious way to say the decade (roaring “twenties”!), ’00s nostalgia, and being able to look back on this post to see how wrong I was about it. I can’t wait!

Art, Physics, and Your Place in the Omniverse

This surreal moment—in which Michael Scott (of the American version of “The Office”) meets David Brent (of the British version)—took place on the American one recently. I thought it was hilarious and apt that they form a hug-worthy bond within seconds of meeting. This was due, I assumed, to them basically being the same person, thrust together by the most divine of chances.

On the website I first saw this at, Nikki’s Finke’s Deadline Hollywood, a commenter named cookmeyer1970 took a less breezy view of it. Although they said they ultimately enjoyed it, they began by saying:

I was very much against this (the two series shared practically the same script for an episode as well as duplicate characters making it, in my opinion, two parallel universes that shouldn’t cross)…

I don’t think the issue of “duplicate characters” really has to come into play—most of the American characters that were adapted from British ones are done so pretty roughly, and even Michael and David have their differences. And by this point, the American show (which has aired 140 episodes) has created a whole swarm of characters that have no equivalent on the British show (which aired 14). But I admit I hadn’t thought about the fact that the first episodes of the two series are identical nearly line-to-line.

Does a fact like that firmly establish that the two “Offices” could not possibly exist within the same plane of being? Should Scott and Brent have destroyed each other like matter and anti-matter the instant they ran into each other?

From a practical standpoint, my answer was: I don’t care. It goes without saying that virtually any TV series requires suspension of disbelief, and as far as potential inconsistencies go, I realize this might be one of the most obscure, technical ones ever. But from a theoretical perspective, I think it’s quite interesting to consider.

You sometimes hear about “the universe” of a particular film, TV series, book, or other work of art. Some of these universes are extremely obvious. Clearly the universe of, say, “The Lord of the Rings” is not our own. But the truth is that literally all stories, even those that might appear firmly grounded in reality, create their own universe that necessarily cannot be the same as our own.

For instance, look at “The West Wing.” Despite relying on ripped-from-the-headlines political issues for much of its drama and intellectual substance, not to mention frequently discussing U.S. history and governmental minutiae, the world it depicted was in some ways as alien as Middle Earth. The show established that Nixon was the last real president its universe shared with ours, and despite incorporating real foreign states into storylines all the time, also invented the countries of “Qumar” and “Equatorial Kundu” to stand in for generalized representations of the Middle East and Africa, respectively. (It also presented a universe in which every human is capable of delivering a searingly witty riposte without a second’s hesitation at any given moment and for any given situation, but that’s another issue.)

Does this mean we should consider “The West Wing” a fantasy? Certainly not. Does it mean we can’t appreciate the voluminous amount it has to say about the real issues in our world? Not in the least. But it’s not our universe, and actually it’s not even particularly close to being our universe.

The divergence point for the universe of a movie or TV show can come from an even more elementary source. Consider the fact that in the universe of any work that involves actors playing characters, it would be fair to assume the actors don’t exist within that work’s universe. The most brilliant, succinct explanation of this concept is found in the underrated existential action comedy “Last Action Hero,” when a kid enters the universe of a Schwarzenegger film. He finds that in a world without Arnold, logic dictates that the Terminator could very well have been played by Sylvester Stallone.

If I remember correctly, there was also a joke on “Seinfeld” once in which Frank Costanza reads about Jerry Stiller dying. This would prove that actors on a show could possibly still exist within that show’s universe, as odd as it would be for George Costanza’s perfect doppelganger to exist and for him to be an actor to boot. But the bottom line is, it wouldn’t be a joke if that wasn’t the case—and it’s only the case in the “Seinfeld” universe.

This idea is a overlapping concept between art and quantum mechanics. They many-worlds interpretation is too complicated, certainly for me, and possibly for anyone, to fully understand, but the basic principle is that every possible outcome of every possible divergence point exists in a universe somewhere within the “multiverse.” In other words, every single thing that could happen does happen, and it creates a new universe when it does. Does this mean that every choice the author of a work of fiction makes determines what real universe, out there amongst countless others, they end up describing? Who’s to say?

(By the way, it’s worth mentioning that the multiverse is, theoretically anyway, not the be-all and end-all. It is “simply” the collection of possible quantum configurations of our universe; it’s conceivable that there are more multiverses, as well as multiverse-type realms in other dimensions, that we don’t understand. The collection of everything, anytime, anywhere, in any dimension, is referred to as the “omniverse.”)

This panel depicting the DC Comics character the Flash existing in different forms in different universes illustrates the "many worlds" concept.

The medium that has undoubtedly explored this concept the most is comic books. Both DC Comics and Marvel Comics have made explicit references to the many-worlds idea and have taken advantage of it in far more ways than just depicting characters with superpowers. They’ve had DC and Marvel characters fighting each other, transported their characters into the Renaissance, and imagined what it would be like if Superman had landed in the Soviet Union rather than America. There was even a storyline in which the Fantastic Four made their way to our Earth, in which Marvel Comics is a company that produces stories about them, to beg “God” (author Jack Kirby) to save a particular character’s life. This is all while within the many-worlds framework, which ends up being an elegant solution to any potential continuity problems—and, incredibly, a scientifically plausible one at that.

I really like the idea that every story that has ever been conceived is part of the actual omniverse. Everything that you have ever imagined has happened. So when it comes to “The Office,” why can’t two office managers, who presided over an episode-long period of strikingly identical events, exist together? It doesn’t make much sense in our universe, but in the “Office” universe? Why not?

The only point I want to make here is this: You can look at the creation of art and fiction as wondrous, magical even, and I certainly do. But you can also look at it in terms of tapping into the most incredible potential realities that science tells us could exist. And I think that’s pretty damn cool.

One of the most amazing stories of “Star Trek” is a Deep Space Nine episode, “Far Beyond the Stars,” in which Captain Sisko has visions of himself as a sci-fi writer struggling to get his stories—about space station Deep Space Nine and its commanding officer, Ben Sisko—published in segregated America. Even if racist editors prevent his work from being published, he insists, his creations still exist because “you can’t destroy an idea.”

It’s the End of MTV as We Know It, and I Feel Fine

The 24th MTV Video Music Awards, held on September 9, 2007, represented some kind of low-water mark in the channel’s history. This edition of the VMAs halved the number of awards, renamed the surviving ones to joky titles like “Most Earthshattering Collaboration” and “Monster Single of the Year” and solidified MTV’s party-all-the-time image by eschewing classier venues like Radio City for the Palms in Las Vegas.

With so many negative MTV elements coming to a head, it may have seemed appropriate when Justin Timberlake, accepting the award for Best Male Artist, expressed what many think is the reason for MTV’s ills. “Play more damn videos!” he said. “We don’t want to see the Simpsons [these ones] on reality television. Play more videos!”

I’ve talked to many people my age who feel similarly. I can see why they do, at least at first blush; I’m as nostalgic about MTV as the next Echo Boomer. But I think when it comes down to it, in today’s world, it’s clear that both we and MTV are better off if they don’t bother too much with videos.

Before MTV launched in 1981, music videos had already been receiving considerable attention in the U.K. on “Top of the Pops” and elsewhere. But in the U.S. the format was mostly unknown, consigned to occasional appearances on variety shows, as between-movie filler on HBO and a pioneering program on the USA Network.

Of course MTV changed that, and the music video would go on to alter the direction of film editing and change fans’ sensory understanding of popular music forever. When it began MTV was basically the only place to see videos and therefore one of the best places around to learn about new music. After copycat shows on broadcast networks fizzled, it remained that way for a long while.

But you don’t need me to tell you that that isn’t the world we live in anymore. The Internet in general, and YouTube in particular, has put you, at this very instant, a few keystrokes away from virtually every music video ever produced.

So to sum up: Then, we had a single video at any given time doled to us by a massive media conglomerate whose primary objective was to garner ratings and get us to buy stuff; today, we have instant access to a Memory Alpha-like historical archive of the artform at any time or location we choose. I don’t yearn for the way of the past when it comes to this, and I don’t know why anyone would.

The movement of music away from the television and onto the Internet has been, in my view, an enormously positive development. When it was the dominant source of music videos, MTV was inert, a cultural master you could either choose to submit to or not. YouTube, music blogs, and the rest of the musical Internet is nothing like that. It doesn’t tell you what culture to consume and offer no alternative; it challenges you to seek out the culture that you, individually, will like the best. And if you accept the challenge (and to be sure, it is far more challenging than watching MTV), I think the results tend to be more rewarding.

Again, I’m sensitive to the feelings of those persons who fondly remember the days of “Celebrity Deathmatch,” “Say What? Karaoke” and videos being labeled “Buzzworthy” or “Spankin’ New,” because I am one. But, in this and many things, we shouldn’t confuse nostalgia with the way things should be now.

Nor should it be confused with a prudent business plan for MTV, not that MTV itself needs that advice. I can see a new Lady Gaga video on probably millions of different websites, but the only place I’m going to watch a new episode of “Teen Mom” (well, legally, anyway) is on MTV or MTV’s website. It’s clear that MTV foresaw this long ago, and if it hadn’t rededicated itself to original programming, there is no way it would be in existence today.

I don’t want to imply that I love what MTV is today, though. “Jersey Shore” is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how its reality programming has devolved into being about partying and little else, and the slow descent of “The Real World” to this territory is especially saddening. Even when MTV tries to consciously go against that impulse, the results sometimes to lead to some of the worst scripted programming I’ve ever seen.

That being said, there are positive things to be said about MTV, and I think what it has become—essentially, a channel catering to teenagers and young adults—is a great thing in theory at least. If “The Real World” no longer has many meaningful things to say about a generation, the prolific “True Life” definitely still does, and this year MTV also received the first “Excellent” rating in the history of GLAAD’s Network Responsibility Index which measures channels’ presentation of LGBT characters and issues.

One more point I’d like to address is the contention that a channel shouldn’t be acronymically calling itself “Music Television” if it isn’t about music. To that I say, you should only believe that if you believe AMC shouldn’t show “Mad Men” because it isn’t an “American Movie Classic” or that CBS shouldn’t show anything unrelated to Columbia Records music, since that was the origin of the name “Columbia Broadcasting System.”

Both of those channels, like MTV, realized they weren’t serving unique enough niches anymore, so they evolved. Just as, over the years, music consumers have evolved to embrace new technologies. Sometimes its messy, but I generally think that, in the end, evolution ends up benefiting everyone. I think even Justin Timberlake would agree with that.

Shockin’ Through the Decades

“Shock rock” is sort of a redundant term. Rock and roll has always been about pushing the envelope since…well, since whenever it began, an unanswerable question that is the subject of a particularly detailed and fascinating Wikipedia article.

Since the world has become comfortable with the idea of rock music, it’s taken a little more to qualify as what anyone would call shocking. Really, is anything shocking anymore? I don’t mean this as a joke. Even if you have never heard of nor wish to seek out the band Fartbarf, the album Carnivorous Erection or the song “Fecal Smothered Dildo Punishment,” I’d imagine it doesn’t truly startle you to know they exist. Feel free to Google them if you don’t believe me.

When a shocking band is out of sight and out of mind for all but the tiniest sliver of society, they haven’t really succeeded in shocking. So what of those musicians who are known to relatively many but still retain the reputation for shock? They tend to be iconoclastic, ego-driven individualists; they tend to have a keen sense of what kinds of shock appeal to mass audiences (themes of death and horror, for the most part) and they tend to have at least a tiny smidgen of actual talent (though not always).

These qualities make up a sector of popular music that has developed less as the domain of true shock and more into a semi-defined, not-always-shocking genre called shock rock. In honor of this, scariest month, I present this rundown of shock rockers throughout history.

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins (first record: 1956)

Most musical genres can’t trace their origins to a single individual (though some can). But the history of shock rock makes it seem reasonably clear that it began with one specific song: Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You.” Like most defining songs of original rock and roll, it straddles the border with rhythm & blues, and has been covered over and over by obvious antecedents and others as well.

The song was originally meant to be a straightforward ballad. It only ended up in the grunting, shrieking, animalistic way it did because both Hawkins and his band recorded the final take in a drunken stupor that he didn’t remember the next day. It was only then that Jay Hawkins became Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and the world was left to wonder once again whether the course of history would have been different had a small group of people not gotten wasted at the precise time they did.

Hawkins also originated a key component of shock rock by opening his act by coming out of coffins, wearing a cape and carrying around a skull-on-a-stick sidekick named “Henry.” Hawkins never came close to replicating the success of “I Put a Spell on You,” but because of that one song and the decades-long career it afforded him, everyone on this list owes him a debt of gratitude.

Screaming Lord Sutch (first record: 1961)

The parallels between Hawkins and Sutch don’t end with having names implying an inclination to utter loud piercing cries. Both were, in their own unusual ways, on the cusp of a significant movement in the development of rock and roll—Hawkins with the gradual breaking-off from African American rhythm & blues, Sutch with the British Invasion—and both were famous primarily for one, oft-covered song.

For Sutch, that song was “Jack the Ripper,” and the song’s subject matter (not to mention Sutch’s caped, top hatted image) established the Victorian motif that would inform much future shock rock. This live performance from 1964 is incredibly surreal to me. The screams of British teenage girls are a familiar emblem of the black-and-white rockin’ ’60s, but how often do we see them elicited not by happiness but by something resembling actual revulsion?

Sutch might be the campiest figure on this list, and he has a few other good songs that stray far into Bobby “Boris” Pickett territory. It’s difficult to find and kind of truly dark undertone to his songs, which is sadly ironic considering he hung himself at age 58.

Arthur Brown (first record: 1968)

Another shock rock progenitor, another one-hit wonder. For Arthur Brown and his band, the quaintly named Crazy World of Arthur Brown, the song was “Fire,” which was a #1 hit in the U.K. in 1968. Someone might prove me wrong, but as far as I can tell, Brown was the first musician to wear bright white-and-black “corpsepaint”-style makeup, which is really pretty significant, when you consider the wide spectrum of later artists who wore it.

I also get the feeling that Brown was the first shock rocker to introduce a level of true menace to his delivery. Hawkins and Sutch were more in your face, but I get more of a sense of creeping dread from Brown. He conducted himself not like a deranged, creepy outsider, but more like a supernatural presence—the “God of Hellfire” as he put it—which is another hallmark of future shock rock.

The alarmingly D.I.Y.-looking pyrotechnic device attached to Brown’s head in the video led to some extremely predictable incidents. For instance, at one show, the inflammable fluid spilled onto his head as he was being lifted to the stage by a crane, and his hair was, as the song puts it, taken to burn. The situation was dealt with in a very rock-and-roll manner when a quick thinking-fan doused the flames with a pint of beer. Not sure if the ordeal took Brown to learn (not to do that anymore). I can’t decide if this is hilarious or an indication of him having been really kind of crazy, but one way or another Brown definitely pushed the genre further.

Alice Cooper (first record: 1969)

We’re now moving away from progenitors and toward some people who should and actually finally might get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Alice Cooper is one of those celebrities who seems to weirdly get more prominent as he gets older, but he wasn’t always the Wayne-and-Garth educating, golf-obsessed, evangelical conservative Republican he became. Come to think of it, he probably was, but the world just didn’t know it.

What it did know at Alice’s inception was that Alice Cooper was a band, not an individual. When the erstwhile Vince Furnier assumed the Alice moniker for himself (apparently a ouija board told him he was the incarnation of a 17th century witch by that name) and wrestled the copyright for it away from his bandmates, he established two shock rock precedents with one fell swoop: a combination of mild transvestism with hyper-machismo, and an ego too large to accept peers.

(His former bandmates have gone on to other things, and I’d feel remiss if I didn’t mention drummer Neal Smith, whose website describes him as a “Rock N Realtor” and has an intro stating, “Over 25,000,000 albums: SOLD. Over $25,000,000 in real estate: SOLD.” Check it out yourself.)

Cooper’s catalog contains some bona-fide non-shocking classics and a bevy of very good ones that tend to combine horror (at varying levels of camp) with intense libidinousness. As he has gotten older and become a sort of scary-music mascot, one might expect his music to have mellowed, but on the contrary, his lyrics seem to have gotten somehow more controversial as he blows past 50 and 60.

I’m not sure how I feel about that. I’d like to give him credit for trying to stay bold and commenting on current events (that song was written in response to the Columbine shootings). But the lyrics are so atrocious that I can’t, and furthermore, the contrast with his new-found family friendly image makes songs like that seem incredibly fake, too. There’s no denying, however, that Alice Cooper was the first shock rock superstar, and I’ll always appreciate him for that, even if he puts out a promotional single about drinking donkey blood with all proceeds going to the Tea Party Express.

Ozzy Osbourne (first record: 1970)

What’s the opposite of a soft spot in your heart? Whatever it is, I have it for Ozzy. I feel weird admitting that since he was the original frontman for one of the most skull-meltingly awesome and influential bands in the history of heavy metal, Black Sabbath, where his singing was acceptable enough to not get in the way of Tony Iommi and company. But I often have wondered—and I hope I don’t get death threats for saying this—how good the band would have been had a singer of the quality of the late, far-beyond-great Ronnie James Dio been with them from the beginning.

Ozzy didn’t really become a shock rocker until he became a solo act. As you can see, this is something of a pattern. Most of the incidents he’s most notorious for—biting the head off a dove, drunkenly urinating on the Alamo memorial in Texas, biting off the head off a bat (that he once claimed he thought was rubber, and that he claimed another time bit him, necessitating rabies shots)—happened after he left Sabbath.

I’ve just never gotten much out of Ozzy other than a party animal with an exceedingly average voice who sometimes likes to wear heavy eyeliner. I see “Crazy Train” as a great 30 second intro that is ideal for a baseball player’s walk-up song followed by four minutes of total stock. I see “Mr. Crowley” (and most of Ozzy’s attempts to delve into the occult) as corniness that wouldn’t sound terribly out of place on a Spinal Tap album.

I actually think one of Ozzy’s best solo songs is “Suicide Solution,” which is a legitimately nuanced and interesting take on alcoholism. The song is a warning that regularly drinking to excess is a form of slow, torturous suicide. But of course, this is the song that more than one dead teenager’s parents have sued him over. Ozzy knew his song wasn’t really at all about suggesting kids kill themselves. But when he titled it as he did, did he have this ensuing controversy in the back of his mind? Knowing his penchant for shock without the substance to back it up, it wouldn’t surprise me.

Kiss (First Record: 1973)

I was planning to only include individuals on this list, since the ego-driven solo artist seems to be the shock rock archetype. But I realized there was no way I could exclude the band that began when an art major named Stanley Eisen met an Israeli-born elementary school teacher named Chaim Witz in Queens.

From a commercial standpoint, Kiss is the perfect shock rock band. They wear strange makeup, they spit blood and fire and play a bass shaped like an axe. But they combine all this with a catalog of songs that is almost painfully inoffensive. Their most famous song‘s lyrics could have been sung by Bill Haley. Yes, there was a brief rumor when they came out that KISS stood for “Knights in Satan’s Service,” but there’s no way in hell (pun definitely intended) that anyone could think that today.

What this sterilized version of shock rock has produced is a repugnant merchandising empire that has weirdly overshadowed the band’s music. But when it comes down to it, while they don’t have a deep collection of hits, they have a few that are pretty damn great. Vacuous and musically simpler than most punk songs, but great. I’m happy to take a visualless Kiss mp3 now and again, but personally I’ll let them keep the condom, the coffeehouse, the licensed professional wrestler and the casket. Sorry, “kasket.”

Grace Jones (first record: 1976)

You can’t really call Grace Jones a shock “rocker.” But her brand of shock pop/disco/new wave introduced the important concept that mainstream shock didn’t have to come from themes of horror or death. Take for example the cover of her second-highest charting album, which features a title that would shock Al Sharpton, a flattop that would shock Kenny Walker and a mouth that would shock the ice cream truck guy in “Legion.”

As you can tell in this video when she wears an enormous Keith Haring dress or Andy Warhol declares that “Grace is perfect,” Jones enmeshed herself into the ’80s avant garde like few other musical artists. She appeared on talk shows wearing enormous orange turbans and gold masks. But at the same time, she appeared in “Conan the Destroyer” and played a salacious, steroidal henchwoman in the James Bond film “A View to a Kill.” She wasn’t tied to any cultural movement as much as she was committed to subverting cultural norms, which was a brilliant calculation for someone who came along right as the world was becoming a bit more shockproof.

In my opinion Jones’ musical output, which is heavy on covers, is a bit inconsistent—I think her version of “Warm Leatherette,” for instance, pales compared to the original, while others are outstanding. But her achievement was not in music or film but in image. She ushered in a new kind of art-and-fashion based shock that reflects in pop to this day and has scarcely ever needed to employ a drop of fake blood. (Well, almost.)

GG Allin (first record: 1977)

GG Allin has the unique distinction of being the only person on this list whose birth name was weirder than their stage name: His name at birth was Jesus Christ Allin. He was born and raised in a no-electricity, no-running water New Hampshire log cabin with a sociopathic religious maniac father who regularly abused his wife and children. And this incredibly sad and evil upbringing produced a person who was, unfortunately, plenty evil in his own right.

Grace Jones’ revelation was that you could attain shock value by subverting cultural norms rather than literally shocking people. Allin was the opposite. There were no homages to old horror movies at his shows. There was literal horror. A typical GG Allin show would feature him stripping naked, committing self-harm, producing every kind of human waste (sometimes, proceeding to consume it) and engaging in violent physical or sexual acts with audience members.

Allin repeatedly promised to top all these by eventually committing suicide onstage, but he died of a drug overdose before he could. I have to admit that his funeral was twistedly poetic: As he lay in repose, his friends plastered stickers on his casket, jammed drugs and whiskey down his lifeless throat, took pictures of themselves touching his penis, and generally treated his bloated, fetid corpse with the same disrespect he treated everyone in life. The consensus was that that was how he would have wanted it.

There are those who hold Allin up as a paragon of individualist punk ethos. But by the end of his career, it seems obvious to me that what he really was was an extreme narcissist who was quite deluded about both the extent of his influence and the consistency of his philosophy. It was his need for attention that led him to take shock rock to its logical extreme. He recorded a few songs, but I’m sure even he knew he was never going to be remembered for his musical talent. For better or for worse, he proved that one can be remembered for shock alone.

Rob Zombie (first record: 1987)

I think it’s possible that Rob Zombie does not get as much respect as he deserves. Paying homage to horror films of the past, campy or otherwise, is a tradition as old as Bauhaus and the Misfits. But I think it was with Zombie, with his band White Zombie and in his later solo career, that it really reached its apogee.

Take, for instance, “Dragula” (named after the Munsters’ car), which I think, in contrast to some of the hard rock my peers and I liked in the late ’90s, holds up exceedingly well today. I feel like this song and video are masterpieces of cinematic schlock-homage. I especially appreciate the fact that Zombie doesn’t seem too self-serious about it, if his “Night at the Roxbury”-style head pump while cruising in the dragula is any indication.

His horror fixation extends beyond exploitation movies; one of my favorite music videos of all time is his one that emulates a silent film. And his old band White Zombie had some pretty bangin’ hits of their own (although I have always thought that the lyric I originally thought it was—”more human, that’s what you’ve been”—would have been cooler).

I think Rob Zombie is the first artist on this list I’d think of as a shock rocker more as a genre label than for someone who generated any actual shock in their time, which is reflected in how the public views the types of films he derives his image from. He’s also more of a multimedia magnate than anyone on this list, as he has branched out to become an in-demand (if not particularly good) film director. (In that vein, there’s also an odd spinoff-like element at work in the fact that what he is to horror, his younger, less-popular brother tries to be to sci-fi.) Zombie might not be high on shock, but ironically, he seems more enmeshed than anyone in the culture and history of what shocks people.

Kembra Pfahler (first record: 1990)

Kembra Pfahler is probably the least well known artist on this list, but I really wanted to bring her up for two reasons. One, I think the picture at left is the most shocking one I saw in my research for this post. And two, she seems to me to be a remarkable synthesis of different shock rock elements. She combines Zombie’s midnight movie motif with Jones’ avant garde artistry with Allin’s transgressiveness with a mastery of makeup and presentation that outstrips almost anyone.

Most of Pfahler’s music has been recorded with her band, the marvelously named Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black (named for the cult icon), who have an array of camp horror-inspired songs with titles like “Chopsley: Rabid Bikini Model” and “Do You Miss My Head” as well as some quite transformative covers. And her music, image and overall presentation is accepted as avant garde art in a way that few musical artists are; she was featured, for instance, during the 2008 Whitney Biennial.

Most (though not all) of Pfahler’s music actually tends to be pretty straightforward and inoffensive relative to her image, but she more than makes up for it with some of her transgressive performance art pieces that would probably have given pause even to GG Allin (who she recorded with, by the way). She’s known, for instance, for cracking eggs on her vulva. Which really only sounds intense if you don’t know that she once literally sewed her vagina shut. (It would seem clear that this was some sort of protest against objectification, yet she also posed for Penthouse in this condition, so count me as confused.)

Finally, it’s also worth nothing that Pfahler is something of a cosmetological celebrity, having appeared at several makeup-industry events. And I think you get a good sense of the concept of shock rock in general when you see a crowd of calm fashion types watch her sing about “suck[ing] the shit out of your ass” while completely naked and covered in red paint (all of those things are in this video, if you care to witness them). I love the idea of someone like her being a cosmetics spokeswoman, even though you’d figure nearly every potential consumer is not looking to get as extreme as her. Sort of like SUV commercials highlighting towing capacity when most suburban buyers will never know the difference. The bottom line is, when it comes down to it, who is makeup more crucial to than shock rockers?

Marilyn Manson (first record: 1994)

If such things could be quantified, I think Marilyn Manson would have had one of the highest name recognition-to-knowledge of his music ratios in music history. It’s hard to imagine any American who was alive in the ’90s not recognizing his name, and his reputation for evil, for being the “Antichrist Superstar” as he himself put it. In an amazing feat of vocabularic gymnastics, Joe Lieberman managed to convey, at the same time, both the horror that conservative parents had for him and the enthusiasm his youthful fanbase had for him when he declared the band to be “the sickest group ever promoted by a mainstream record company.”

Yet, I sense his music remained invisible to most. I blame Manson himself completely for this, as his bible-ripping antics and album covers depicting himself as a hermaphroditic nude extraterrestrial were part of an overwhelming strategy of shock. But what separated him from older shock rockers, who some jaded music fans said he was simply a rehash of? For me one answer is a sense of humor. Manson had none of Ozzy’s partying spirit or Alice’s joie de mourir. Manson presented himself as a truly grim figure, and with his rod-straight hair, pasty makeup and everpresent weird contact lens, he looked considerably more alien. I only know of one press photo-type picture of him smiling, and it’s not exactly what you’d call humanizing.

In recent years Manson has become more accessible (sometimes in rather inexplicable ways). But I think it’s too bad that his extreme image turned off so many from his music, which is in some instances quite interesting in my opinion, and also can be quite different from what most people think of when they think of him. The album that launched him to stardom, Antichrist Superstar, is full of the goth-ish, pseudo-sacrilegious stuff everyone remembers like the still-powerful song whose title references the Beatles’ “Baby You’re a Rich Man”. But I think his next album Mechanical Animals, a glam, Warholian meditation on fame and popular culture, is masterful, and I still listen to songs on it like “The Speed of Pain” and the title track.

Until not too recently I used to wonder if, given how severe his look was, Manson could possibly age gracefully. Then one day I looked up and realize I’m already sort of getting an answer. As his look wears off and his days as conservative America’s worst nightmare recede ever farther into the past, I’m sure Manson the public figure will fade more and more into obscurity, which I’m perfectly fine with. But I think his work deserves to be remembered.

Lady Gaga (first record: 2008)

What past musical artist is Lady Gaga most like? Lots of people have opinions. Madonna? Seems obvious enough. Bowie? It’s written right on her face. And the name “Lady Gaga” is a reference to a Queen song.

Of course, all of these are right. But I also want to suggest that, much like dinosaurs evolving into birds, she is the seemingly incongruous descendant of everyone on this list. The most clear precedent is Grace Jones, and Jones herself certainly agrees. But she also maintains the pointless religious iconography, the obsession with celebrity and the practice of looking bizarre in public that many shock rockers, and I’d say in particular Manson, share.

She’s actually already done a forced-sounding remix with him (I’d love to know what a real song by the two of them would sound like). And just like Manson graduated from subverting norms to grand, conceptual shock weirdness, Gaga seems to have definitely done the same.

Manson flamed out quickly, and that makes me wonder if Gaga will too. My feeling is that her brand of non-horrific shock will work for a lot longer. And even though it has seemed for decades that the genre is close to the end, I sense that somehow or other shock rock will work for a lot longer too.

A Retrospective of ’90s Kids’ Sports Movies